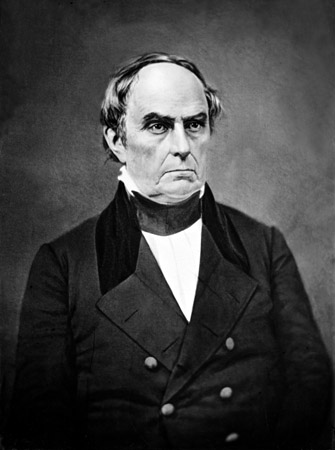

Daniel Webster’s Compromise

What ruined the pre-civil war politician Daniel Webster? Early on he argued that humility before God and honoring justice would require men to oppose slavery. But decades of compromised political action reduced him to an embarrassment of a man, who by moral relativism now claimed that slavery was perhaps just a difference of opinion. In his 1820 Plymouth Oration 1

, this cousin of lexicographer Noah, Webster rightly declared that “neither the fear of God nor the fear of man exercises a control” in the hearts of those wishing to extend slavery. He called upon Americans to “cooperate with the laws of man, and the justice of Heaven” through efforts “to extirpate and destroy” the wicked institution. Webster's fiery orations inspired many in the North to take strong stances for the elimination of slavery.

What ruined the pre-civil war politician Daniel Webster? Early on he argued that humility before God and honoring justice would require men to oppose slavery. But decades of compromised political action reduced him to an embarrassment of a man, who by moral relativism now claimed that slavery was perhaps just a difference of opinion. In his 1820 Plymouth Oration 1

, this cousin of lexicographer Noah, Webster rightly declared that “neither the fear of God nor the fear of man exercises a control” in the hearts of those wishing to extend slavery. He called upon Americans to “cooperate with the laws of man, and the justice of Heaven” through efforts “to extirpate and destroy” the wicked institution. Webster's fiery orations inspired many in the North to take strong stances for the elimination of slavery.

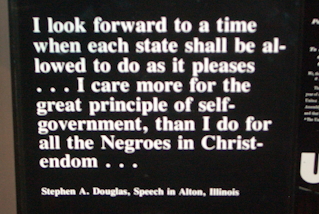

Thirty years later, he was less resolute. It seemed abolition was a distant hope and that slavery was firmly ingrained into American society. By the time a junior Illinois Senator named Stephen Douglas proposed an omnibus slavery bill, Webster was ready to join what became known as the Compromise of 1850.

Thirty years later, he was less resolute. It seemed abolition was a distant hope and that slavery was firmly ingrained into American society. By the time a junior Illinois Senator named Stephen Douglas proposed an omnibus slavery bill, Webster was ready to join what became known as the Compromise of 1850.

In a speech that he considered one of the most important in his career, Webster criticized abolitionists as extremists who, by agitating Southerners, created tensions that threatened the Union. Unlike his strong denunciations years before of slavery as a moral evil, the Senator now portrayed disagreements only as a “difference of opinion” and questioned even man's ability to know which side was right with any kind of moral certainty. He claimed:2

In all such disputes, there will sometimes be found men with whom every thing is absolute; absolutely wrong, or absolutely right. … They deal with morals as with mathematics; and they think what is right may be distinguished from what is wrong with the precision of an algebraic equation. … They are apt, too, to think that nothing is good but what is perfect, and that there are no compromises or modifications to be made in consideration of difference of opinion or in deference to other men's judgment. … [They are] too impatient always to give heed to the admonition of St. Paul, that we are not to "do evil that good may come.'3

Doing a little evil so that some future potential good might occur ignores the fact that there can be no compromise on basic moral principles. Daniel Webster, who once excited men to hold fast to the justice of heaven, now ridiculed purists who refused to compromise their morals. Scripture is clear that moral considerations take precedence over political expedience.

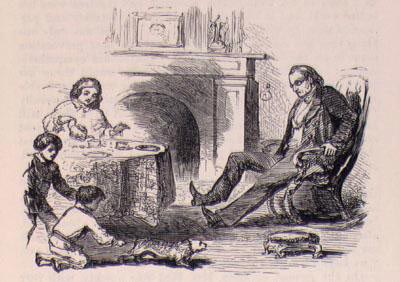

One of the stipulations of Douglas' Compromise Bill was tougher enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. It was this law that inspired a line of dialogue in Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, in which the character Senator John Bird tries to convince his wife that returning escaped slaves to their masters is a moral imperative for Christians. She objects:

One of the stipulations of Douglas' Compromise Bill was tougher enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. It was this law that inspired a line of dialogue in Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, in which the character Senator John Bird tries to convince his wife that returning escaped slaves to their masters is a moral imperative for Christians. She objects:

Mary Bird: “Now, John, I don't know anything about politics, but I can read my Bible; and there I see that I must feed the hungry, clothe the naked, and comfort the desolate; and that Bible I mean to follow.”

Senator John Bird: “But in cases where your doing so would involve a great public evil—”

Mary Bird: “Obeying God never brings on public evils. I know it can't. It's always safest, all round, to do as He bids us.4

Mrs. Bird knew what Webster had forgotten. Rather than falling to the temptation of compromise, we are to follow Christ’s example and choose the good that God has provided to us in every choice or circumstance. Just like on the issue of slavery, pro-life advocates should not compromise on God's enduring moral commands including, Do not kill the innocent. Rather than doing evil that good might come, we must always “seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness."5

See also, What does the Bible say about Slavery? and here at AmericanRTL.org:

- Dred Scot Shepardized: Informing Pro-life Strategy

- Anti-Slavery Garrison: Instructs Pro-lifers, and

- Hear this Slave "George Stephens" Pro-life Radio Ad

Audio file

- 1Daniel Webster, "The Plymouth Oration speech" Plymouth, Mass., Dec. 22, 1820, linked to at Dartmouth College.

- 2Daniel Webster, "The Constitution and The Union" Speech to Congress, Washington DC. March 7, 1850. U.S. Senate with searchable text at Google Books in "The Works of Daniel Webster," pages 331-332.

- 3Romans 3:8 quoted by Webster.

- 4Harriet Beecher Stowe, "Chapter IX: IN WHICH IT APPEARS THAT A SENATOR IS BUT A MAN." Uncle Tom's Cabin. Boston: John P. Jewett, 1852. 122. Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture. University of Virginia. Web.

- 5Jesus Christ, Matthew 6:33, New King James Version